You are not alone.

After decades of use, people just accept assumed differences between GGIs and HGIs as actually existing.

I'd like to point out the similarity between these two types of grease interceptors because this will make it easy to identify mythical assumed differences for what they are.

They both use gravity-differential separation

Have you ever jumped into the air and not landed on the ground again? Unless you live somewhere other than on planet earth, you are subject to gravity the same as the rest of us.

If there is no gravity then the earth doesn't revolve around the sun, the moon doesn't revolve around the earth and there is no point in reading any further because there is no such thing as human beings either, which means no one needs to be concerned about how grease interceptors work.

My guess is that we have all proven that gravity exists at least once in our lives.

An object with a specific gravity of less than one will float in water while an object with a specific gravity of greater than one will sink. This is also very easy to prove. Here is a list of some common specific gravities:

If you are going to experiment with any of these, I recommend you properly dispose of them when you are finished as most of these are prohibited from discharging to sanitary sewer systems, at least here on earth (if you are not here then you may need to check your local planetary requirements on that).

Gravity-differential separation simply means to use the differences in specific gravities of restricted pollutants, such as fats, oils and grease (FOG) as the means of separation from water inside an interceptor.

Grease poured into a static body of water will rise very quickly to the surface based on the size of the bubbles formed, their specific gravity, their viscosity and the temperature of the grease and water. The rise rates of the bubbles is predictable according to Stokes law.

Grease poured into a static body of water will rise very quickly to the surface based on the size of the bubbles formed, their specific gravity, their viscosity and the temperature of the grease and water. The rise rates of the bubbles is predictable according to Stokes law.The difference between a static body of water and a grease interceptor is that the water in the interceptor is not static. The discharge from a connected fixture will have a flow rate that must be dealt with in a grease interceptor.

A Symposium on Grease Removal titled Design and Operation of Grease Interceptors by Frank Dawson and A.A. Kalinske, published in 1944 explains the fundamentals of gravity-differential separation in grease interceptors as follows:

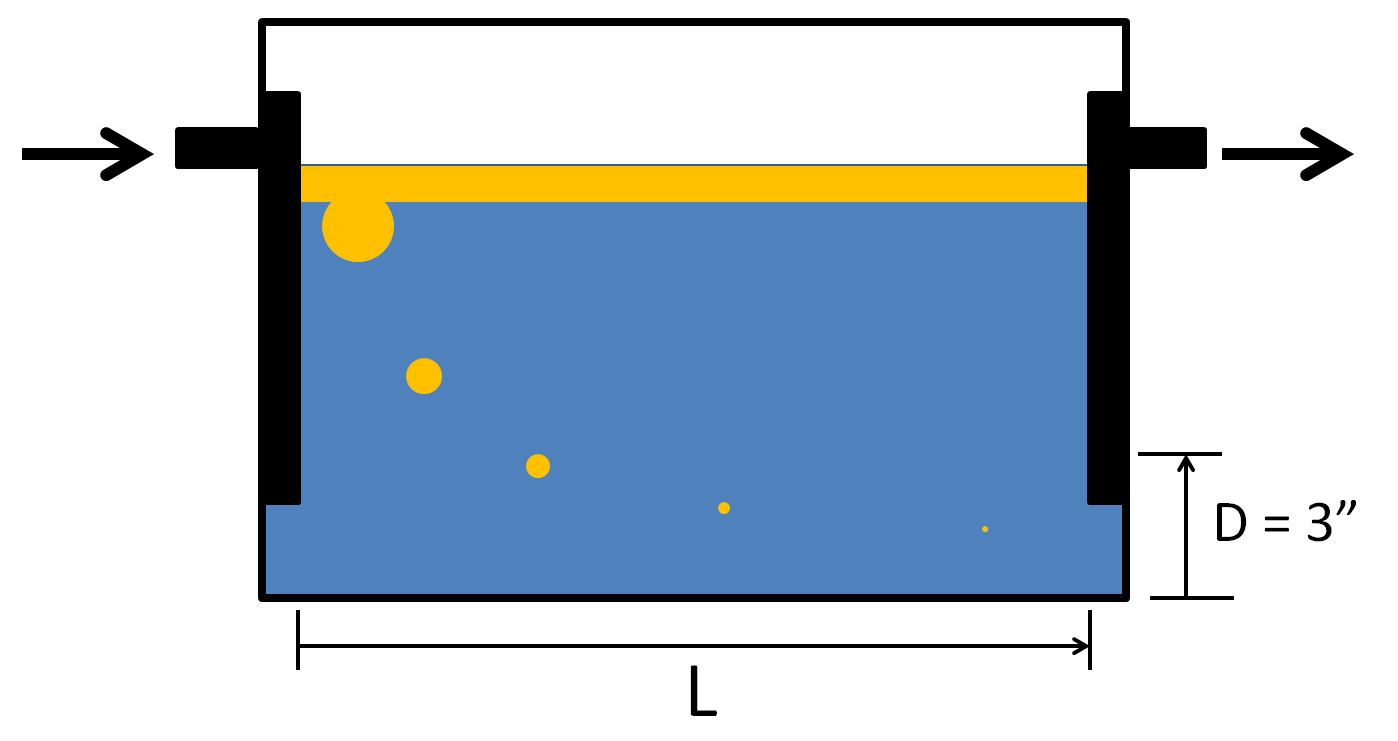

"For simplicity let us assume that pure grease and water enter near the bottom of a rectangular-shaped interceptor L feet long, B feet wide, and with a water depth of D feet. The interceptor will do a good job of separation if, as the flow goes through the interceptor, the mean velocity of flow is such as to permit the grease globule to rise a vertical distance D in a length of L feet."

Dawson et al. went on to say, "If we neglect, for the moment, the presence of turbulence we see that the controlling item in the sizing of the interceptor for any particular rate of flow is the rate of rise of the grease globules. If the size of the globules is known, the maximum velocity of rise can be calculated readily from known principles of fluid mechanics, by equating the buoyant force on a globule to the force of fluid resistance."

If I keep quoting Dawson et al. we are all going to be asleep soon. So let me paraphrase from here. Velocity is the speed that the fluid is moving across the interceptor. If the fluid moves too quickly the smaller grease globules are less likely to have time to rise an adequate distance to remain in the interceptor. This makes velocity a key to good interceptor design.

The American Society of Plumbing Engineers (ASPE) established three inches as the minimum distance D that a grease globule must rise in a length of L in an interceptor to be retained (ASPE Plumbing Engineering Design Handbook 4, Plumbing Components and Equipment, Chapter 8 Grease Interceptors).

Gravity-differential separation applies to any grease interceptor regardless of manufacturer or type. HGIs must be designed based on this principle and so do GGIs.

No exceptions.

So what is the assumed difference?

That HGI's use controlled flow and some other stuff, most of which is bunk (counter-current flows, bernoulli's equation, etc.), to do what GGIs do with retention time.

Assumption debunked.

HGIs control the incoming flow and distribute it throughout the cross-sectional area reducing the fluid velocity to allow for gravity-differential separation at the maximum rated flow of the interceptor.

GGI's do not!

This is basic physics.

GGIs simply take whatever flow is dumped into them and everyone assumes that, no matter what, the GGI can handle it.

Sorry, it ain't possible.

Uncontrolled inlet velocity and the associated turbulence causes short-circuiting at higher flow rates in GGIs. This is not to say that GGIs don't work. At lower flow rates they work very well because turbulence decay happens rapidly at low flow rates. At higher flow rates though, turbulence decay happens over an exponentially longer time.

Experiments by the Water Environment Research Foundation, included in their 2008 report Assessment of Grease Interceptor Performance, demonstrated that residence times of at least one hour were more conducive to turbulence decay in the standard IAPMO approved GGI (Z1001) design.

When everyone finally steps back long enough to think clearly about how all grease interceptors must actually work - we will finally be able to start focusing on what is really important in an interceptor (hint - it isn't how much water it can hold).

When everyone starts focusing on how efficient a grease interceptor is and how much grease it can hold instead of how much water it can hold, we wont need to worry about whether its called an HGI or a GGI because all grease interceptors will be just grease interceptors.

HGIs will not hold just 2 lbs of grease for each 1 gpm of flow rate - because to keep up with competition, they will have to hold 5 times as much or 10 times as much or even more!

If GGIs are the FOG abatement solution of the future then the earth doesn't revolve around the sun and the moon doesn't revolve around the earth and we don't exist either, which is weird because my back hurts.

Hi, Ken

ReplyDeleteReally nice post,

I want to tell you that I am also with those persons who thought that Gravity Grease Interceptors (GGI) are better than Hydromechanical Grease Interceptors (HGI). But after reading this article my thoughts regarding GGI and HGI got cleared.

Thank you so much

Am I missing something here, I am studying this and think I must be missing the point somewhere. Brown Grease Study 2011. Portland Oregon indicates influent strength 10000 mg/L FOG not exceptional. Flow of 75 litres a minute over the peak period of 4 hours equates to 18000 litres of wastewater. This would then require the HGI to retain 162 kilograms of FOG. Seems a lot of capacity for an under bench trap?? Wouldn't chemically emulsified grease pass through a HGI anyway??

ReplyDeleteHello Mick, 162 kg is a lot of FOG (357 lbs) for an under counter type HGI. This is the very reason that I argue that all fixtures should be routed to an interceptor - that necessarily eliminates an under counter sized device - and it ensures that the FSE cannot bypass the grease interceptor with FOG discharges directly to the collection system. And YES chemically emulsified grease is more likely to pass through a grease interceptor - it's the nature of the chemical bond and the reduced surface tension of both the oil and water affected.

ReplyDelete